justin_le said:

Buk___ said:

You went from elastic to plastic deformation.

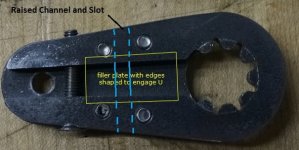

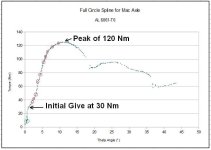

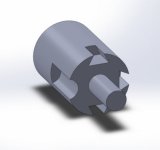

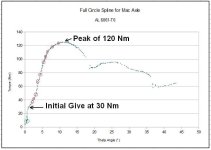

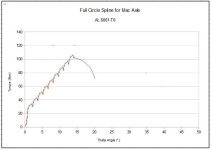

No it's not just that, it's an actual rolling motion that was possible after one end tooth broke off at 30 Nm and then there was room for sufficient displacement that overall shape of the opening could change, allowing the axle to turn without actually shearing off any additional teeth. That's what I was trying to emphasize. If you look at the actual shape of the torque vs. displacement curve at this point it's not a normal case of transforming form elastic to plastic deformation.

If you sheared a tooth, you definitely went from elastic to plastic; and then way beyond.

After that, the addition degree(s) of freedom meant that the fulcrum effect of the next two teeth to contact applied the load in a direction that caused plastic deformation in the U-shaped TA; basically levering the sides apart and due to the opposing fulcrums, distorted the head of the U, so that the sides translated in opposite directions.

justin_le said:

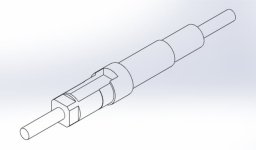

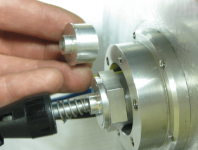

The results with an identical aluminum torque plate interface but constrained so that the axle stayed in same central axis as the torque plate didn't show this, and went right up to 120 Nm before there was any plastic deformation. Then when it did fail, almost all the teeth sheared. I'll do another example where the arm is just pulled steadily to failure rather than pulsed to failure.

I would interpret your torque/theta graph somewhat differently. I believe it shows the transitions from elastic to plastic many times as each new pair of contact points come under load as the previous exceed the yield point and shears:

At each of those red circles, there is a transition in the forces. Initial a sharp reduction, then a steady build leading to the next red circle. My interpretation of that is each circle is where the elastic limit of one tooth is exceeded, it shears, there is a drop in torque as the shaft rotates a few minutes of arc until it connects with the next tooth.

Then the elastic limit of that tooth fields the force, and the tooth stretches sidewise until it reaches the yield point and the process repeats. I count 10 red circles for 10 pairs of teeth.

(There is also something going on in the green circle at the start of loading? Could be the strain cell loading up, or slack in the system.)

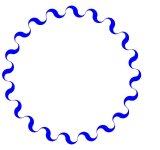

I suspect (would put money, but don't have access to the equipment to perform the test to prove it). that if you could apply the torque very much more slowly and steadily, and if the resolution of your stress.vs.strain graph was higher, you would see a graph something like this:

Of course it is an idealised representation, but basically:

- the stress/strain rises steadily at a slope equaling the materials modulus of elasticity;

- the yield point is exceeded and the slope lessens as you transition through the plastic range and the material permanently deforms;

- the shear plane finally lets go and the tooth shears;

- the torque drops and the rotation increases suddently as the shaft rotates to the point that the next pair of teeth engage;

- the graph returns to the Young's modulus slope because these new teeth have yet to experience any stress;

- the process repeats until enough teeth have sheared to allow the shaft to rotate freely.

justin_le said:

What type, temper and thickness of Al are you using?

It's 6061 T6, 3/16" thick, but not because that's a material we plan to use. This is just sacrificial testing to see relative strength of various designs when the material is held fixed, and then once the design is optimized we'll see what material is then most suitable. If it can be Aluminum (perhaps 7000 series), then that would be great just because we can more easily do all the fabrication in house.

Understood about it's sacrificial nature.

However, without labouring the point, even if you get a 7000 series part to survive the torque test, I'd still caution against it. Even if you went to 7075-T6 with its ~450MPa yield strength, it will still embrittle with cyclic nominal loading;

and will fail! And at a loading far below the T6 critical value.

I get the ease of manufacture point, but trade that against liability?

I can do no better than link and quote this again.

Long ago, engineers discovered that if you repeatedly applied and then removed a nominal load to and from a metal part (known as a "cyclic load"), the part would break after a certain number of load-unload cycles, even when the maximum cyclic stress level applied was much lower than the UTS, and in fact, much lower than the Yield Stress These relationships were first published by A. Z. Wöhler in 1858.