Lock

100 MW

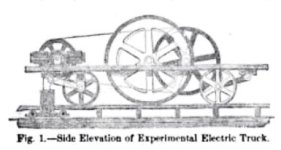

In the `80's (1880's), in the UK road locomotives with accumulators (ebikes) didn't make a lot of sense with the Red Flag laws that limited speeds to 4mph (2 in town) etc. Electric omnibuses were of interest, but where battery-electrics developed a lot of interest was on the water, in competition with the smokey noisy smelly steam engines used on powered river launches at the time... Here's some reports from technical journals etc:

The Marine Engineer, November 1, 1882

The Marine Engineer, August 1, 1883

The Marine Engineer, August 1, 1883

The Marine Engineer, October 1, 1883

No word on how Major Macliver made out with his plans to cruise to the Black sea... Lloyds recorded several boats registered in 1883 with the "Clark's Patent Electric" system:

The Marine Engineer, November 1, 1882

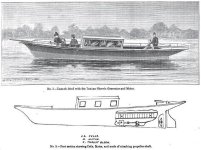

An Electric Launch. - Professor Sylvanus P. Thompson has written an account of a trip on the Thames in a launch propelled by electricity. He says:- "At half-past three this afternoon I found myself on board the little vessel Electricity, lying at her mooring off the wharf of the works of the Electrical Power Storage Company at Millwall. The little craft is about 26 ft. in length, and about 5 ft. in the beam, drawing about 2 ft. of water, and fitted with a 22-in. propeller screw. On board were stowed away under the flooring and seats, fore and aft, 45 electric accumulators of the latest type as devised by Messrs. Sellon & Volckmar. Fully charged with electricity by wires leading from the dynamos or generators in the works, they were calculated to supply power for six hours at the rate of 4-horse power. These storage cells were placed in electrical connection with two Siemens dynamos of the size known as D3, furnished with proper reversing gear and regulators, to serve as engines to drive the screw propeller. Either or both of these motors could be 'switched' into circuit at will. In charge of the electric engines was Mr. Gustave Phillipart, jun., who has been associated with Mr. Volckmar in the fitting up of the electric launch. Mr. Volckmar himself and an engineer completed, with the writer, the quartette who made the trial trip. After a few minutes' run down the river, and a trial of the powers of the boat to go forward, slacken, or go astern at will, her head was turned Citywards and we sped silently along the southern shore, running about 8 knots an hour against the tide. At 37 minutes past 4 London Bridge was reached, where the head of the launch was put about, while a long line of onlookers from the parapets surveyed the strange craft that without steam or visible power, without even a visible steersman, made its way against wind and tide. Slipping down the ebb, the wharf at Millwall was gained at one minute past 5, thus in 24 minutes terminating the trial-trip of the Electricity. For the benefit of electricians I may add that the total electro-motive force of the accumulators was 96 volts, and that during the long run the current through each machine was steadily maintained at 24 amperes. Calculations show that this corresponds to an expenditure of electric energy at the rate 3 1.11-horse-power."

The Marine Engineer, August 1, 1883

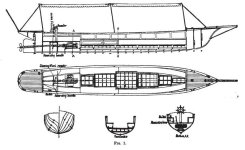

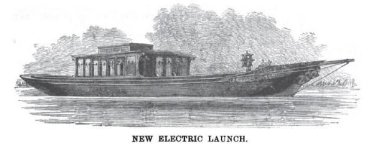

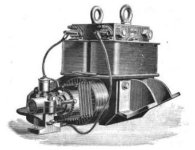

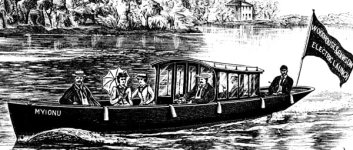

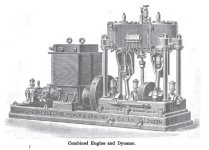

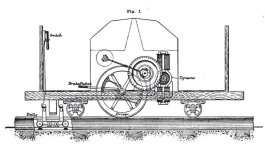

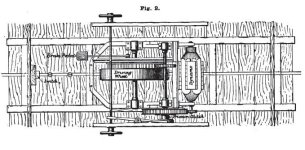

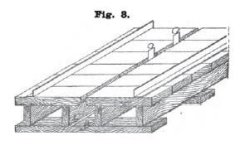

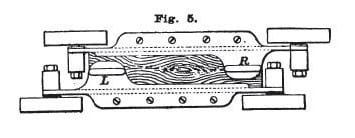

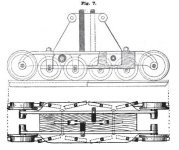

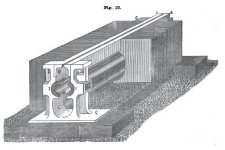

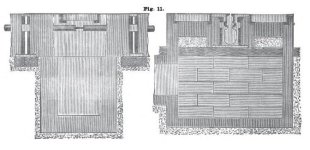

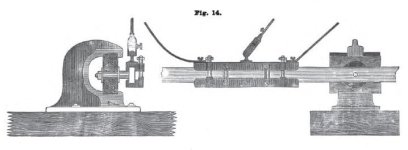

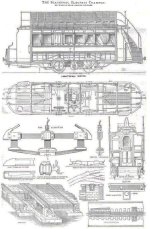

The Electrical Power Storage Company has by no means been discouraged with its former tentative experiments for the driving of launches by electricity. We see that this Company, in conjunction with Messrs. Yarrow & Co., have lately launched a new and handsome boat intended for the Vienna Exhibition. The launch is 40 ft. long by 6 ft. beam, and has a 3 ft. draught of water aft. The screw is 18 in. diameter with 13 in. pitch, and is driven at 680 revolutions per minute by a Siemens' dynamo, commutated as a motor. No gearing is used, the spindle of the armature being coupled direct to the end of the screw-shaft. The thrust-block is just aft of the dynamo, the whole being placed under the floor in the sternsheets of the boat. The power was supplied in 80 Sellon-Volckmar secondary batteries or accumulators, which weighed 60 pounds each, or about two tons together with the dynamo. This may be taken as fairly corresponding with the weight of an ordinary engine and boiler and propeller to drive such a launch at the speed required, which was an average of over seven miles an hour, though on the measured mile a speed of over eight was obtained. The whole of the secondary batteries are put away out of sight under the lockers under the seats, and under the floor of the launch, so that as the motor is covered by the sternsheets, no batteries or engine are visible. There is no smoke, no dust, nor steam, no smell of oil nor splashing of pumps, and the whole arrangement is perfectly noiseless, except the bubbling of the water caused by the revolution of the propeller running at such a high speed. As the battery charge would suffice for six hours' constant work, we may consider the problem has thus been solved of producing an electrical launch which amply suffices for pleasure purposes, with all the advantage of the greatest possible accommodation for passengers, and a total absence of smell and "blacks" which are so annoying in the ordinary steam launch. While the working of this system is in its infancy, no doubt the serious disadvantage of the electrical launch chancing to have used up its store of energy without a possibility of renewal, will strike the ordinary observer, but as soon as the system should be generally adopted, there is no reason why stations for the storage of electrical power might not be as accessible upon the river as is at present the ordinary supply of coals. It is quite possible that the combination of a motor of such simple parts with the propeller will enable engineers to arrive at important results with regard to the percentage of work absorbed in the ordinary launch engine, as apart from the efficiency of the propeller. The enormous speed produced by the little motors will enable propellers of exceedingly fine pitch to be driven at such high rates of revolution as cannot possibly be obtained with the reciprocating steam-engine.

The Marine Engineer, August 1, 1883

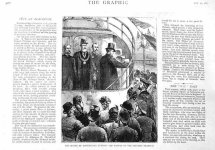

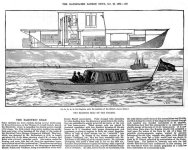

AN ELECTRICAL LAUNCH.

On July 17th this little boat, intended for the Vienna Exhibition, made a run from the Temple Pier to Greenwich in thirty-seven minutes, with a moderate tide. Some delay was, moreover, caused by the propeller fouling a basket, an event well known to every one who has had any experience with steam launches on the Thames. The distance is six miles, so that making allowance for the tide, it may be said that a speed of over seven miles an hour was attained, and full power was not employed save for a portion of the time. On the measured mile an average speed of over eight miles an hour has been obtained.

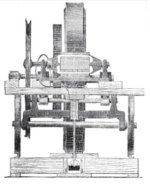

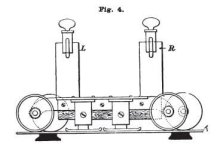

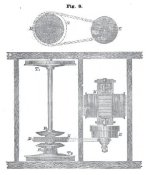

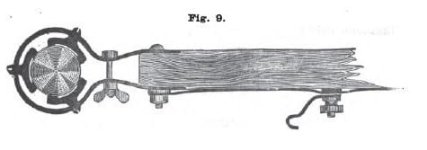

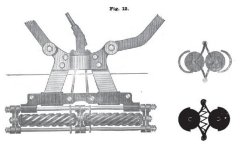

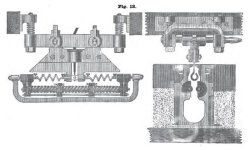

The boat is 40 ft. long and of good beam. She had twenty-one persons on board, including the steersman and a man to look after the machinery, if such it may be called. The boat is completely unincumbered from end to end, no trace of the propelling mechanism being visible. This consists of eighty cells of Sellon-Volckmar accumulators, of which fourteen are disposed under the seats, seven at each side, and the remainder in the bottom of the boat under the floor. The screw is turned by an a Siemens' dynamo commutated as a motor. No gearing is used, the spindle of the armature being coupled direct on to the end of the screw shaft. The thrust block is just aft of the dynamo, which is placed under the floor in the stern sheets. It lies flat, and occupies very little space. There are four brushes, two for going ahead, two for going astern, and two small lines going to a becket beside the steersman enable him at a moment's notice, by pulling one or the other, to go ahead or astern; a cylindrical switch beside him enables him to stop or go on at pleasure. This switch is graduated so that the current from forty, sixty, or eighty cells can be used at pleasure. The weight of the whole - batteries and dynamo - is about two tons, or as nearly as possible that of engine, boiled with water, and coal for a steam-engine competent to propel her at the same speed.

This pretty launch is the very perfection of a pleasure boat; no heat, no smoke, no dust, no steam, no smell of oil, no splashing of pumps. There is no noise of any kind to be heard save the bubbling of the water from the propeller, and the faint hiss caused by the commutator rubbing against the brushes. There is no smell, and no "blacks;" and the boat will run for six hours continuously, or about forty-five miles.

During the trip to which we are referring the current passed through the dynamo was 41.22 amperes from sixty cells, the electromotive force being 112.5 volts, and (41.22 x 112.5)/746 = 6.21 H.P. The loss by friction, &c, must be very small, for 6 indicated H.P. could certainly not have propelled the boat at the speed she readily attained. It has long been known that the screw is an extremely wasteful propeller. It may yet be that further investigations will show that the screw is not so much to blame as the combination of screw and engines. At any rate the system of electrical propulsion opens up a new field of inquiry, because it renders possible the use of screws of extremely fine pitch revolving at a great speed. The dynamo in Mr. Yarrow's boat makes about 680 revolutions per minute. The propeller is of steel, two-bladed, 19 in. diameter, and 13 in. pitch. There is absolutely no vibration, and very little disturbance of the water in the wake of the boat.

No matter what may be the opinions formed concerning the utility of the electrical propeller for commercial purposes, there can be no doubt that the Electrical Power and Storage Company and their manager, Mr. Collett, and Mr. Yarrow, have together proved that the system is admirably adapted for pleasure purposes. In fact, for such work as that now done by steam launches on the Thames, the electrical system is simply perfection. The expense will be, on the whole, about that of steam; but to those who keep steam launches expense is a secondary consideration, and it must not be forgotten that a 20 ft. electrical launch will afford at least as much accommodation as a 30 ft. steam launch. Thus in Mr. Yarrow's boat, quite 11 ft. of the best part of her would be occupied by engines and boilers. As to the supply of storage cells, that can easily be managed. Many private gentlemen could keep their own engine and dynamo on shore to do the charging, and for the rest it would suffice to establish at certain places on the banks of the river, as at Kingston, Staines, Maidenhead, &c, depots where, during the summer season, dynamos driven by stationary engines would keep on charging batteries. By calling at any of these stations, enough power for a six hours' run could be obtained either by charging the cells in the boat direct, or by taking the run-down cells out and replacing them with charged cells.

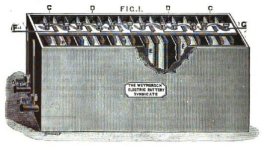

We may add that certain very important improvements have been made in the Sellon-Volckmar accumulator. As now made they have an E.M.F. of 2.3 volts, per cell at starting, and will give five ampere-hours per pound of battery - a very admirable result.

The Marine Engineer, October 1, 1883

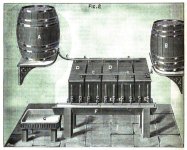

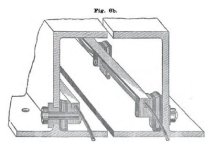

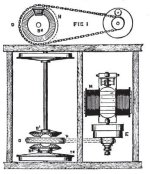

Electric Launches. - On September 10th Messrs. Gilbert, Bogle & Co., of Glasgow, tried one of their electric launches on the Clyde at Kilcreggan. It was driven by Clark's patent battery and engine, Mr. Clark, the patentee, himself managing the machinery and also steering the boat. The only other persons on board were Mr. Bogle and Major Macliver, of Bristol and London, for whose inspection the trip was made. Clark's patent dispenses with dynamo machines and accumulators, which need re-charging, and enables the motion to be kept up by refilling the batteries with a simple chemical compound. In the smaller boats a speed of from five to seven miles is attainable, and Major Macliver, who had with him a 15-ft. launch, built for him by Power & Douglas, of Waukegan, Illinois, has ordered it to be fitted with Clark's machinery. If the experiment be successful, Messrs. Bogle are to construct a much larger vessel for him, which it is intended to take through the canal between the Rhine and the Danube next year, to make the trip from the German Ocean to the Black Sea through these rivers and their artificial junction. The large boat will be designed for a speed of ten miles an hour, and it will take several months to construct her, but the smaller one will probably be seen on the Thames before the end of October. Major Macliver believes that he can make the trip from ocean to ocean in about three weeks, and intends to do so without any assistance whatever.

No word on how Major Macliver made out with his plans to cruise to the Black sea... Lloyds recorded several boats registered in 1883 with the "Clark's Patent Electric" system: