thewmatusmoloki

10 kW

Cool headlight

A NEW LIGHT 0N ELECTRICITY.

A chat with Professor Ayrton, F.R.S.

From Cassell's Saturday Journal.

Electricity is in the air, and half the world seems to be electrically mad. Since the debut of the motor car, almost every topic of conversation - North, South, East and West has had some reference to electricity. Prophets have arisen, and if they do not belie their name, we are going to have electricity in everything. Electric boots to propel our legs, electrical clothes

dusting machines, dummy servants run by electricity - these are a few of the devices which are promised us.

There is some danger, however, in our expecting too much from the mystic current, and when I wrote to Professor Ayrton, the celebrated scientific expert, requesting an interview with him, I had it in my mind to ask him for some definite information on the subject of the uses of

electricity. Professor Ayrton most kindly acceded to my suggestion, and with rare good nature permitted me to question him for a full hour.

"What electricity is going to do depends on a variety of circumstances," the professor replied, in answer to a question as to the future of electricity. "That it appeals more successfully to the public than it did some years ago admits of no doubt. But the progress of electricity has been retarded to an enormous extent by the vast sums which were wasted at the commencement of the enterprise. Many bogus companies with wholly impossible schemes,

with which it was never intended to do any real work, were foisted on ths public, who were robbed wholesale. Then the reaction followed; people regarded electricity with disfavor, and nothing was done for a time. However, the great thing is, we are going ahead at last."

"A lot of people are going about just now advising us to cook our meals by electricity. Do you advise us to respond to their honeyed pleadings, professor?"

"Electricity has no future for cooking, unless it be for very occasional purposes. There are, of course, all sorts of electric appliances for heating water, grilling chops, etc., but none of them is likely to come into general use under present conditions. Some time ago, I made various

experiments with the object of ascertaining the cost of heating water by electricity as compared with that of heating water by gas. Now, the cost of electrical energy, as everyone knows, is from sixpence to eightpence per board of trade unit, which is about the same as one horse-power exerted for eighty minutes. No company in London can legally charge more than eightpence per unit, and in many districts the maximum charge is made. Well, for the purposes of my experiments, I took the cost of the board of trade unit at the low figure of fourpence, and the price of gas at half a crown per thousand cubic feet, and I found that it costs twenty-five times as much to keep water boiling by electricity in an ordinary electrlc kettle as it does by gas - and this, it must be remembered, when fourpence only is charged per unit, a price which has hitherto been almost unheard of in London."

"Then it won't pay to use electricity for any domestic purpose save lighting?"

"Well, not at any rate for general cooking, for if you get the energy at fourpence per board of trade unit, it wouldn't pay you to run your kitchen fire electrically as a regular thing. There are, however, one or two cases where the convenience is so great that for intermittent warming it might be worth while to employ electricity. If a man did not care to have gas in his

room, for instance, he might use electricity for heating shaving water, or a lady might prefer an electric kettle on her tea table to one heated with a spirit lamp. Although the electricity would be more expensive than gas, the whole cost would be so small that few would probably mind paying it. But when you have continuous heating electricity under existing conditions, it is hopeless. "

"I have said." the professor continued, "that to run kitchen fires by electricity would be too expensive; but there is just one other exception which is worth mentioning. When you have a waterfall close at hand, your conditions are favorable to the use of electricity. In this contingency you are not called upon to burn coal. Imagine a hotel near a waterfall, the power of which is running to waste all day. In a case of this kind it might pay you to warm that house electrically. There is the power at hand - you get it free of cost. If you pay nothing for the power you need not mind how lavish you are. You may take it from me that there is no

chance at present of producing heat for domestic purposes economically by electricity."

"What, then, is electricity going to do for us in the near future?"

"What we shall get in the immediate future are underground electric railways. Quite a number of these have already been proposed, and we may look for their development at no great distant date. Electric traction is going to be the big thing. You will scarcely credit it, but there are only eleven electric lines in the United Kingdom at the present time. In the United States there are 10,000 miles of electric tram lines, and up till very recently there were more electric tramways in the city of Montreal than in all France and Germany. This is partly accounted for by the fact that people in our large towns will not stand the overhead trolley wires, and because other systems of laying down electric cables along the lines are so expensive. Now, however, a new system is coming into operation, and we may expect speedy developments."

I now turned the professor's attention to the subject of electric cabs, of which so much is expected.

"I don't think the electric cab has any future," he replied,"that is, unless we have some wholly new invention. No electric vehicle which does not get its power of propulsion from overhead wires or underground conductors can compete with steam or petroleum traction. If I wanted a motor car to-morrow I should buy a steam or petroleum one. I shouldn't dream of getting one whose power was drawn from accumulators."

"You can see my point for yourself. To develop a board of trade unit of energy in a motor car driven by means of accumulators would, after allowing for the wear and tear of the cells, etc., cost about a shilling. If the same work were done by means of coal it would cost something like a penny. You see, the cost of the renewal and repairing of the accumulators, which electric cabs must use to move their wheels, is the very serious obstacle."

"Now as to electric bicycles and tricycles, professor. Are they possible?"

"If you ask me if I can make one, I answer 'Yes.' But if you mean will I use one I say emphatically 'No.' In 1882 I constructed an electric tricycle and I used to run it in the streets near my office in the city during the evening when the traffic was small, and when the police were less imperative about its being preceded by a man carrying a red flag. That electric tricycle was sent over to Paris and it may still be in existence. But nothing will make electric bicycles and tricycles worth using - of course, in comparison with those driven by steam or petroleum. They haven't the chance."

"Before I go out into the gaslight myself, professor, will you tell me if we are soon going to see the end of gas?"

"I do not think it probable that we shall dispense with gas yet awhile. The incandescent burner is a very great rival of the electric light; but though it is not ousting electricity it has to be taken into serious consideration. It is rather curious to note that nothing has done the gas companies so much good as the electric light. About sixteen years ago, when people thought that the electric light was going to extinguish gas for all time, the shares of the gas companies went down to about half their value. To-day the companies are paying bigger dividends than ever. The reason of this is that the standard of illumination has been raised. Immediately people saw the electric light they, of course, wanted more illumination and used

more gas burners."

1888 Fred Kimball

Philip W. Pratt demonstrates the very first American electric tricycle.

Pratt’s e-trike was built for him by Fred M. Kimball of, naturally, the Fred M. Kimball Company. Pratt took the editor of Modern Light and Heat for a spin around Winthrop Square in Boston.

The vehicle’s 10 lead-acid cells pushed about 20 volts to a 0.5 horsepower DC motor. The whole setup weighed about 300 pounds.

The driver sat above the battery assemblage. Top speed: 8 miles an hour.

However, an electric vehicle was in operation in the East as early as 1888, the brainchild of an obscure yet prolific inventor, Philip W. Pratt. His patents included the rubber chair tip, the rubber crutch tip, rubber heel plugs, machines for making rubberized cloth, and several types of nonskid tires. Mr. Pratt may indeed deserve the title of "father of the American electric automobile." His invention might well have gone unnoticed but for the journalistic professionalism of the editor of a short-lived Boston magazine devoted to the wonders of electricity, Modern Light and Heat. Writing in the issue of August 2, 1888, the editor noted, "We received an invitation last Friday from a gentleman who is giving much attention to electric vehicles--Mr. P.W. Pratt of Boston--to take a ride on an electric tricycle that had just been completed for him by a well-know electrical manufacturing concern of this city."

Power was supplied by "six cells of the Electrical Accumulator Company's storage batteries, weighing all told, 90 pounds and a specially constructed tricycle motor connected to the driving apparatus by chain gearing." The date of this demonstration of Pratt's electric tricycle thus was July 27, 1888. Until an earlier claimant surfaces, that date and Mr. Pratt's name deserve to be added to the record books. Unfortunately, no additional information about this machine appeared in Modern Light and Heat. Nor have any images of this conveyance survived, other than a contemporary artist's sketch. The Pratt tricycle later was shown to the public in New York's Central Park and Atlantic City. Mr. Pratt was negotiating for the licensing of one of his patents when he died in Boston in 1915 at the age of 75. Found in his room at the Hoffman House with an illuminating gas jet half turned on, his death was ruled accidental.

Parisian electrical precision instrument maker, Gustave Trouve, arrived on the scene. In May 1880 he patented a small 11lb (5kg) electric motor and described its possible applications (Patent N°136,560). Trouve suggested using two such motors, each driving a paddle wheel on either side of the hull. Later he progressed to a multi-bladed propeller. Modifications to this master patent date from August 1880, then March, July, November and December 1881. To quote: “It is the rudder containing the propeller and its motor, the whole of which is removable and easily lifted off the boat…â€Â

With this invention, Trouve could not only lay claim to the world’s first marine outboard engine but, in taking the same motor and adapting it as the drive mechanism of a Coventry-Rotary pedal tricycle or velocipede, Trouve also pioneered the world’s first electric vehicle. On 1 August 1881 Trouve made his benchmark report to the French Academy of Sciences, stating: “I had the honour to submit to this Academy, in the session of 7th July 1880, a new electric motor based on the eccentricity of the Siemens coil flange. By suggestive studies, which have allowed me to reduce the weight of all the components of the motor, I have succeeded in obtaining an output which to me appears quite remarkable.

A motor weighing 5kg [11lb], powered by 6el of Plante producing an effective work of 7kgm per second, was placed, on the 8th April, on a tricycle whose weight, including the rider and the batteries rose to 160kg [352lb] and recorded a speed of 12km/h.

The same motor, placed on the 26 May in a boat of 5.5m long by 1.2m beam [18 x 4ft], carrying three people, give it a speed of 2.5m [per second] in going down the Seine at Pont-Royal and 1.5 m [8 & 5ft] in going back up the river. The motor was driven by two biochromate of potassium batteries each producing 6el and with a three-bladed propeller.

On the 26th June 1881, I repeated this experiment on the calm waters of the upper lake of the Bois de Boulogne, with a four-bladed propeller 28cm [11 ¼in] in diameter and 12el of Ruhmkorff-type Bunsen plates, charged with one part hydrochloric acid, one part nitric acid and two parts water in the porous vase so as to lessen the emission of nitrous fumes. The speed at the start, measured by an ordinary log, reached 150m [490ft] in 48 seconds, or a little more than 3m [10ft] per second; but after three hours of functioning, this had fallen to 150m in 55 seconds and after five hours, this had further fallen to 150m in 65 seconds.

One bichromate battery, enclosed in a 50cm [20in] long case, will give a constant current of 7 to 8 hours. There is a great saving of fuel and cleanliness.â€Â

During the 15 years that followed, it is estimated that over 100 Trouve electric motors were installed in pleasure launches. Some of these were fitted with his electric headlights and klaxons. There was, for example, the Sirene, a charming electric boat which he built for Monsieur de Nabat, arranging it so that her owner could change at will from propeller to paddles. This boat, whose owner used her three times a week during long periods, measured 29ft 6in long by 6ft beam (9 x 1.8m) and cruised regularly at between 8 ½ and 9 ½ mph (14-15km/h), her propeller turning at between 1,200 and 1,800 rpm.

To show the speed with which an electric boat could move in a race situation, on 8 October 1882 a Trouve craft was launched onto the River Aube and steered onto the race circuit only five minutes before the start. It left at gunfire and spectators noticed, not without astonishment, that in this famous race the boat covered more than 2 miles (3.2km) in 17 minutes, averaging 7mph (11km/h) and slowing down to make four turns around the buoys!

In September 1888 a Trouve boat was sent to China to fight against opium smuggling on the China Sea. 49ft (15m) long and steel-hulled, it weighed some 8 tons and the bronze prop had a diameter of about 20in (500mm). One can but wonder at the electric power necessary to shift her along.

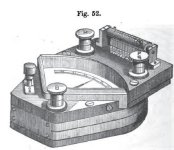

Electric Tricycles.  Last week the passers by were astonished at seeing a tricycle electrically lighted and electrically propelled going down Queen Victoria Street. The source of the electric current was a few Faure's accumulators resting on the footboard, the electric lamps, of which there was one on each side of the tricycle, were incandescent lamps, giving each about four candles, and the electro-motor was one of those recently devised by Profs. Ayrton and Perry, and was fastened under the seat which was occupied by one of the inventors. One speciality of these motors is their compactness and the large amount of power they can furnish for their weight, the total weight of the quarter-horse-power motors, with the Faure's accumulators necessary to propel the tricycle with its rider at the ordinary speed, as well as to electrically light it, being only, we understand, about 1 1/2 cwt., or but little more than that of a second rider.

ELECTRICAL TRICYCLE.

To The Editors of The Electrical Review.

Sirs,  In your last number you favoured your readers with the news of an experiment made with Messrs. Ayrton and Perry's tricycle. The subject of road locomotion by electric energy is of immense interest to all classes. I venture, therefore, through your columns to ask Prof. Ayrton to enlighten the public with fuller particulars concerning this "invention." How many cells do they use to drive their motor, what current and electromotive force, how many hours will the vehicle run on a level road  at what speed, when once charged? What may be the weight and actual power of their motor, what kind of gearing is used to run at any reduced speeds?

A sketch in your valuable paper would prove most instructive. Since the machine has already been exhibited in the streets, there cannot be any further secret about these details. Yours obediently,

A. RECKENZAUN, C.E.

October 30th, 1882.

ELECTRICAL TRICYCLES.

To the Editors of The Electrical Review.

Sirs,  What is the use of an electric tricycle? The Locomotives (Roads) Act, Section 3, enacts that "every locomotive propelled by steam, or any other than animal power, on any turnpike road or public highway, shall be worked according to the following rules and regulations amongst others, namely: Firstly, at least three persons shall be employed to drive or conduct such locomotive; secondly, one of such persons while any locomotive is in motion shall precede such locomotive on foot by not less than 60 yards, and shall carry a red flag constantly displayed, and shall warn the riders and drivers of horses of the approach of such locomotive, and shall signal the driver thereof when it shall be necessary to stop, and shall assist horses, and carriages drawn by horses, passing the same." And by Section 4, the speed at which such locomotives shall be driven along a highway is limited to four miles per hour, and through a city, town, or village to two miles per hour. Is this how electric tricycles are proposed to be driven? That a tricycle is a locomotive within the meaning of the Act of Parliament if driven by other than animal power has been recently decided by the Queen's Bench in the case of Parkyns v. Priest, 7 Q.B.D., 813.

Yours, &c,

CHANCERY LANE.

October 31st, 1882.

ELECTRIC TRICYCLES.

To the Editors of The Electrical Review.

Sirs,  Your correspondent, "Chancery Lane," may well ask "What is the use of an Electric Tricycle?" if in this fast age one is to be compelled to travel at the ignominious rate of four miles per hour and have an avant coureur with a red flag to announce our coming to Hodge and his cart-horses.

Of course we all know that the Act of Parliament was aimed at traction engines, steam rollers, and such like noisy but useful monstrosities, and not at the useful and natty tricycle or any other form of velocipede driven by electricity. The Court of Queen's Bench, however, in their wisdom have decided that tricycles driven by other than animal power do come within the meaning of the Act, and that any person using one except in compliance with the provisions thereof is liable to a penalty not exceeding ten pounds.

Now I take a great interest in electric tricycles, and I quite agree with Mr. Reckenzaun that the subject of locomotion by electric energy is of immense interest to all classes, and being so impressed, I, in my blissful ignorance of the law, set to work to build one, when all at once to my horror and consternation (and I have no doubt to that of many other similar workers in the same cause) came the decision in Parkyns v. Priest. My friends consoled me with the belief that the case would be appealed, and the decision upset. For confirmation of this view I had an interview with my lawyer, but all I got from him was a shake of the head. I frantically endeavoured to impress upon his legal mind the difference between a traction engine and a tricycle, but he refused to be convinced, and pointed grimly to the words of the Act, "other than animal power." These words seemed to haunt me like Banquo's Ghost, and I began to consider their insertion in the Act as a kind of personal

injury, until, one day, a happy thought struck me, which ultimately developed into a practical idea; this I embodied in a specification and submitted it to my grim lawyer, who returned it to me with a grin, and an expression of opinion that an electric tricycle built upon my improved plan would not be an infringement of the Act, but with the natural caution of his class, advised a conference with counsel. A connsel, well-known and respected by most inventors, was thereupon consulted, and my lawyer's opinion fully confirmed. A specification has in consequence been duly filed, and in due course will be made public.

I have only mentioned the above trifling facts for the benefit of our legal friend "Chancery Lane," who, doubtless, has been having a good chuckle over the electricians and their tricycles; but for the information of others I may state that the principle of the invention is the use of electricity as a simple auxiliary, thus reducing the "animal power" required for propulsion to a minimum, but so arranging the machine that without such "animal power" (however small) being exerted continuously the tricycle remains motionless.

I hope to have a machine made on the above principle completed in time for the approaching exhibition, I shall then have great pleasure in sending you full particulars, with diagrams, weight, &c, if you consider the matter of sufficient interest to your readers.

Yours, &c,

JNO. MACDONALD, C.E.

...when all at once to my horror and consternation (and I have no doubt to that of many other similar workers in the same cause) came the decision in Parkyns v. Priest.

PARKYNS v PREIST

[DIVISIONAL COURT]

7 QB D 313

HEARING-DATES: 4 July 1881

4 July 1881

INTRODUCTION:

CASE stated by a metropolitan police magistrate, under 20 & 21 Vict. c. 43.

The appellant, Sir Thomas Parkyns, Bart., who was the owner and inventor of the motor tricycle, was charged under five summonses: (1.) With being the owner of a locomotive propelled by steam on a public highway, which locomotive was not worked according to the rules and regulations in s. 3 of the Locomotives Act, 1865 (28 & 29 Vict. c. 83) and s. 29 of the Highways and Locomotives (Amendment) Act, 1878 (41 & 42 Vict. c. 77), which require that “at least three persons shall be employed to drive or conduct such locomotiveâ€Â; and “one of such persons while the locomotive is in motion shall precede by at least twenty yards the locomotive on foot. …â€Â:

(2.) With unlawfully driving a locomotive propelled by steam through a town at a greater speed than two miles an hour contrary to s. 4 of the Locomotives Act, 1865:

(3.) With a breach of the Locomotives Act, 1865, s. 7, which requires that “the name and residence of the owner of every locomotive shall be affixed thereto in a conspicuous mannerâ€Â:

(4.) With a breach of the Highways and Locomotives (Amendment) Act, 1878, s. 28, subs. 1, which requires that “a locomotive not drawing any carriage and not exceeding in weight three tons shall have the tires of the wheels thereof not less than three inches in width,†and of subs. 4, which requires that “the driving wheels of a locomotive shall be cylindrical and smooth soled …â€Â:

(5.) With a breach of the Locomotives Act, 1861 (24 & 25 Vict. c. 70), s. 12, which requires that “the weight of every locomotive … shall be conspicuously and legibly affixed thereon.â€Â

The five summonses were by consent heard together. The facts proved are set out in the judgment. The question for the Court was whether the machine was a locomotive within all or any of the sections referred to.

COUNSEL:

June 20. Mellor, Q.C. (Channell, with him), for the appellant. The machine was invented after, and was clearly not contemplated by, the Locomotives Acts, 1861, 1865, and 1878. Those Acts dealt with heavy machines drawing waggons, steam rollers, and the like; such locomotives emit smoke to the annoyance of passengers, or injure roads by their weight: s. 8 of the Act of 1861, and s. 28 of the Act of 1878. The legislature could not have intended that a tricycle should be preceded by a man with a red flag. The definition of “locomotive†in s. 38 of the Act of

1878 – “any locomotive propelled by steam or by other than animal power†– must be read with reference to the then state of knowledge. “Propelled by steam†means by steam only, and not (as here) by steam as an auxiliary. If taken literally that definition would include a clockwork engine. In Taylor v. Goodwin n(1) a bicycle was held to be a “carriage†within 5 & 6 Wm. 4, c. 50, s. 78, because the case came within the mischief of that Act, but here it is not so. In Williams v. Ellis n(2) a bicycle was held not to be a carriage. If this tricycle is a nuisance it can be stopped at common law or under the Locomotives Acts.

Leese, for the respondent was not heard.

Cur. adv. vult.

July 4. The judgment of the Court (

PANEL: Lord Coleridge, C.J., Pollock, B., and Manisty, J

JUDGMENTBY-1: Lord Coleridge, C.J.

JUDGMENT-1:

Lord Coleridge, C.J.: ,

JUDGMENTBY-2: Pollock, B.

JUDGMENT-2:

Pollock, B.: , and

JUDGMENTBY-3: Manisty, J.

JUDGMENT-3:

Manisty, J.: ) was read n(3) by

JUDGMENTBY-4: LORD COLERIDGE, C.J.

JUDGMENT-4:

LORD COLERIDGE, C.J.: This is an appeal against the conviction of the appellant by a metropolitan police magistrate under five summonses, whereby the appellant was charged with using a certain locomotive propelled by steam, being a motor tricycle, upon a public highway, without observing the conditions prescribed by s. 3 of the Locomotives Act, 1865 (28 & 29 Vict. c. 83), and s. 29 of the Amending Act of 1878 (41 & 42 Vict. c. 77), and by other enactments. It was admitted before the magistrate and before us, that those conditions had not been observed; and the only question raised for our opinion is whether the machine in question was rightly held by the magistrate to be a locomotive within the meaning of these sections. The first of these provides that “every locomotive propelled by steam or any other than animal power on any turnpike road or public highway, shall be worked†according to certain rules and regulations thereinafter contained. Sect. 29 of the second Act repeals a portion of s. 3 of the first Act, and substitutes another regulation to be observed while the locomotive is in motion, but by s. 38 the word “locomotive†is again defined as meaning “any locomotive propelled by steam or by any other than animal power.†The tricycle in question is described in paragraph 8 of the case before us, wherein the evidence of the respondent is set out. He says that he “saw propelled in the public highway, at the rate of about five miles an hour, a tricycle on which was sitting a man working treadles with his feet in the manner in which tricycles are usually propelled. He noticed some metal boxes under the seat of the vehicle, but when the vehicle passed him he saw no sign of steam and heard no noise. The metal cases contained a small steam engine and boiler and a condensing apparatus, and he saw that the steam was up on the occasion.â€Â

On the part of the appellant, Mr. Bateman, an engineer and machinist, was called as a witness. He described the machine as being like an ordinary tricycle, and capable of propulsion in the ordinary way by the feet of the rider, but with auxiliary steam power to assist the rider, which steam power was, however, sufficiently powerful to move the vehicle if desired without the foot motion. In a metal case (size about two feet by two feet by nine inches) placed below the level of the seat and near the feet of the rider is a small copper tubular boiler and an engine. The fuel used is gas evolved from methylated spirit or mineral oil, in the same manner as in the contrivance known as the Whitechapel lamp. There is therefore no smoke, and the exhaust steam instead of being blown off into the atmosphere, producing the puffing noise common to locomotives, is discharged into a coiled pipe in another metal case behind the rider’s seat, and is there condensed and returned by a small pump to the boiler as hot water, thus at once economising water and fuel and preventing escape of steam into the atmosphere. The power of the engine was about one horse power indicated, and it was capable of driving the vehicle on a level road at a rate of nearly ten miles an hour, but not more. When the vehicle was so driven there was nothing to indicate that it was being worked by steam power, and nothing which could frighten horses or cause danger to the public using the highway beyond any ordinary tricycle.

The weight of the machine was proved to be about two hundred-weight, and the tires of the wheels about an inch and a half in width being similar to bicycle wheels, but somewhat stouter and stronger. The tires being of indiarubber no injury would be done to the surface of the road by working the machine on it.

It was further proved that the machine was fitted with a brake sufficiently powerful to stop the machine in a very few yards against the power of the steam even if it continued working. This was effected by the brake having a powerful leverage, so that a force far less than the force of the steam applied to the brake would nevertheless stop the machine. The brake is also fitted with an automatic action, by which when the weight of the rider is off the seat, the seat rises and thereby applies the brake, so that when there is no person sitting on the seat the brake is applied and prevents the machine moving. The machine is guided by a handle, and can be turned completely round in twice its own length. The boiler is tested to bear a pressure of 700 lbs., and it is habitually worked with a pressure of about 150 lbs. Even if the boiler did burst, being tubular and of copper, the only result would be a rent in one of the tubes, and there would be no explosion.

In answer to questions put to him on behalf of the appellant, Mr. Bateman explained that the principle of the invention was capable of extension to larger carriages, but that the use of indiarubber tires practically limited the weight to something not greatly exceeding the weight of this particular machine, and also that the fuel used could not be used economically to obtain very much greater power than was obtained.

It seems scarcely necessary to do more than to read this description, in order to shew that the tricycle in question comes within the words of the above statutes as being “a locomotive propelled by steam, or any other than animal power.†It cannot be less within this description because it is capable of propulsion in the ordinary way by the foot of the rider, it being expressly found in the case that the steam power was sufficiently powerful to move it if desired without the foot motion. It was argued however, on behalf of the appellant, that such a machine could not have been within the contemplation of the framers of the statutes in question, which apparently were intended to be directed against the use of locomotives larger in size and heavier in weight, and therefore more dangerous to persons using the public highway, than the locomotive in question. It is probable that the statute in question were not pointed against the specific form of locomotive which is described in this case. Indeed, such a locomotive was not known when they were passed, and possibly not contemplated. As, however, it comes within the very words of the statutes, it

seems to us that we cannot upon any true ground of construction exclude it from their operation; and it may be observed that even if the fullest scope be given to this argument, Mr. Bateman’s explanation that the principle of the invention was capable of extension to larger carriages, would shew that a locomotive similar in construction and principle to that which is the subject-matter of this case might by reason of its size and power become much more dangerous; and if this be so, the question to be considered in each case would not be whether the locomotive in question properly came within the language of the statutes; but whether, by reason of the size or weight of the particular machine, it came within the mischief supposed to be contemplated, which shews that such an argument is vicious.

Two cases were cited by counsel for the appellant; but, in truth, they have no bearing upon the present case. The first was that of Taylor v. Goodwin n(1) , in which it was held by this Court that a person riding upon a bicycle on a highway at such a pace as to endanger the life or limb of passengers may be convicted of furiously driving a carriage under the provision of the Highway Act (5 & 6 Wm. 4, c. 50, s. 78). The argument in that case turned wholly upon the meaning of the word “carriage†in that Act, and it gives us no assistance. The second case was that of Williams v. Ellis. n(2) In this case, where a local Turnpike Act imposed a toll upon every horse, mule, or other beast, drawing any coach, sociable, chariot, berlin, &c., it was held that a bicycle was not a carriage liable to toll under the Act. This case was decided upon the ground that the carriages referred to in the statute must be carriages ejusdem generis with the carriages previously specified. This does not appear to us to have any material bearing upon the question now before us.

We think that the decision of the magistrate was correct, and that the conviction should stand with costs.

DISPOSITION:

Conviction affirmed.

SOLICITORS:

Solicitors for appellant: Milne, Riddle, & Mellor.

Solicitors for respondent: Gregory, Rowcliffe, & Co.

n(1) 4 Q. B. D. 228.

n(2) 5 Q. B. D. 175.

J. M. M.

Lock said:Circa 1890 electric:

blueb0ttle2 said:I thought of building something like this just for lols.

Lock said:`Case yer wondering Loser Boy Parkyns couldn't afford a good lawyer apparently...

THE STEAM VELOCIPEDE.

The steam tricycle shown in the accompanying engraving, which wc borrow from La Nature, was invented and constructed by Sir Thomas Parkyns, who called it "The Baronet." The apparatus consisted of an ordinary tricycle, to which was adapted a small tubular boiler placed horizontally a little to the rear of the seat, between the two large wheels, and which was heated with petroleum; of a water reservoir, which served at the same time for condensation, by means of a worm; and of a cylinder with truck actuating three gearings, which, in controlling one another, gave motion to the wheels of the tricycle. The apparatus was arranged so as to be actuated with the feet alone, with the engine alone, or by the combined action of the feet and engine. Moreover, it required the action of the feet to start the tricycle going.

Messrs. Bateman & Co., of Greenwich, who were commissioned by Sir Thomas Parkyns to construct his steam tricycle for sale, have been obliged to modify the whole structure of it before offering it to the public; for the inventor, although he possessed excellent ideas and knew how to apply them, was lacking in the special knowledge necessary for the construction of a machine practically adapted for working.

These engineers began by studying the steam tricycle very closely, and, by modifying the form of certain parts and strengthening them, and by replacing the horizontal boiler with a recently invented very powerful rotary motor, they hope in about six months to be able to offer the trade a steam tricycle which shall be perfectly irreproachable as to construction, security, and speed.

Sir Thomas Parkyns' velocipede could scarcely exceed a speed of seven to nine miles an hour, but the new manufacturers desire to make it attain a speed of thirteen miles, and to thus give it the power of ascending declivities of a certain grade, so that it will not bo necessary to combine the action of the feet with that of steam. They will retain the mode of heating by petroleum, as this has the advantage of giving a fire easy to keep up, of giving out no smoke, and of permitting a large amount of fuel to be carried within little space.

Messrs. Bateman & Co. would have carried their studies of the new steam tricycle much further ere this had they not been overburdened with urgent work, and especially had there not been a law in England forbidding the use of any steam motor on the streets unless it was preceded by a person on foot and ran at a maximum speed of three miles per hour.

The inventor hopes, however, before long to obtain permission for the steam tricycle to run without restriction, seeing that it emits no smoke, gives off no steam (owing to its condenser), will make but little noise, and will have the appearance of one of those ordinary tricycles that are met with in so great number in the streets of London.

WORTMANN SPECIFICATION.

"This invention relates to a new vehicle, which is to be propelled by the upper or lower extremities of the person or persons which it supports, and which is provided with a fly-wheel in such a manner that the same may at will be thrown into or out of gear. This fly-wheel will gather power in going down-hill, and will then give it up in going up-hill, tliereby facilitating the ascending of hills, and preventing too great rapidity while going down-hill.

" The invention consists in the general combination of parts, whereby two persons may be accommodated on the vehicle, and also in the aforementioned arrangement of the fly-wheel.

" When the fly-wheel is thrown into gear, as afore-said, it will serve to gather power, to facilitate the riding up-hill, and to steady the motion down-hill.

" 2. The fly-wheel K, mounted on a separate shaft, J, the sliding pinion f, in combination with the lever g, substantially as herein shown and described, for the purpose specified.

"The above specification of my invention signed by me, this ninth day of June, 1869.

" Simon Wortmann."

" To all whom it may concern :

"Be it known that I, F. H. C. Mey, of Buffalo, in the county of Erie and State of New York, have invented a new and improved Dog-Power Vehicle.

" This invention relates to vehicles which move from place to place on roads, pavements, etc., and consists in an improved construction thereof.

" A is the driving-wheel, which in this instance is in the front of a vehicle having three wheels, but may be in the rear, if preferred, or in any other location.

"The animals being placed in this tread-rim, as represented in Fig. 2, and caused to work, will impart motion to the wheel and to the vehicle, as will be clearly understood.

" Having thus described my invention,

" I claim as new, and desire to secure by Letters Patent,-

" The combination of wheel ABC with a pair of wheels and body to form the running-gear of a vehicle, in the manner shown and described.

F. H. C. Mey.''

" To all whom it may concern :

" Be it known that I, John Otto Lose, a subject of the Emperor of Germany, residing at Paterson, in the county of Passaic and State of New Jersey, have invented certain new and useful Improvements in One-Wheeled Vehicles.

" My invention relates to a unicycle or one-wheeled vehicle, without spokes, which will carry one or more persons, as well as a bicycle or tricycle, and which is operated from within, carries the passenger inside, and only one wheel touching the ground. I attain these objects by the means of the devices illustrated in the accompanying drawings,

" When the machine is not in operation, it will stand by itself, for the treadle and driving wheels being heavier than the idler-wheel H, H will rise and the front part of platform will drop, and the treadle-wheels will rest on the ground."

" I may operate my unicycle by either clock-work or steam, instead of foot-power.

"A small boiler may be placed under the platform 0, with steam-pipe to convey the steam to the inner rim of the large wheel."

What’s made of bicycle parts, weighs 350 pounds, and is self-propelled? Not your typical 1880s vehicle. Before George Long, a carpenter in Northfield, Massachusetts, built this one-of-a-kind experiment, he and other inventors built heavy, steam-powered wagons. So why switch to thin, spidery body materials? Long borrowed technologies developed for the high-wheel bicycle craze, which was just taking off. Bicycles were lightweight; for Long’s three-wheel wonder, a tubular steel frame and spoke wheels meant a better power-to-weight ratio and easier travel on rough dirt roads. Adult-size tricycles were safer, more comfortable, and easier to mount than high-wheel bicycles, so Long’s vehicle pointed the way toward practical, powered road transportation.

Unfortunately, Long’s horse-owning neighbors didn’t appreciate his meanderings in the strange contraption, and Long dismantled it. He received a patent in 1883, and although the steam tricycle never entered production, Long, who lived until 1952, was celebrated as an American automobile pioneer. John Bacon, a steam vehicle collector and historian, reassembled the Long steam tricycle and placed it in the Smithsonian. Today it is a treasured time machine from an era when Americans conceived of alternatives to trains and horses.

Roger White is Associate Curator in the Division of Work and Industry at the National Museum of American History.