Scooters have captured the attention of motorists throughout the world. In addition to their quirky and often endearing styling, the diminutive two-wheelers are affordable, maneuverable, extremely economical to operate, simple to park or store, and often easier to license and register than cars or motorcycles. Thanks to their mechanical simplicity and wide availability, scooters have long played a vital role in the pursuit of personal mobility throughout the world. Not surprisingly, they outsell automobiles in many areas and are even a preferred means of family transportation in places like India, Pakistan, China, and elsewhere. In the United States scooters are becoming increasingly popular as gas prices continue to rise and the motoring public seeks a new way to proclaim their individuality and personal style on a budget.

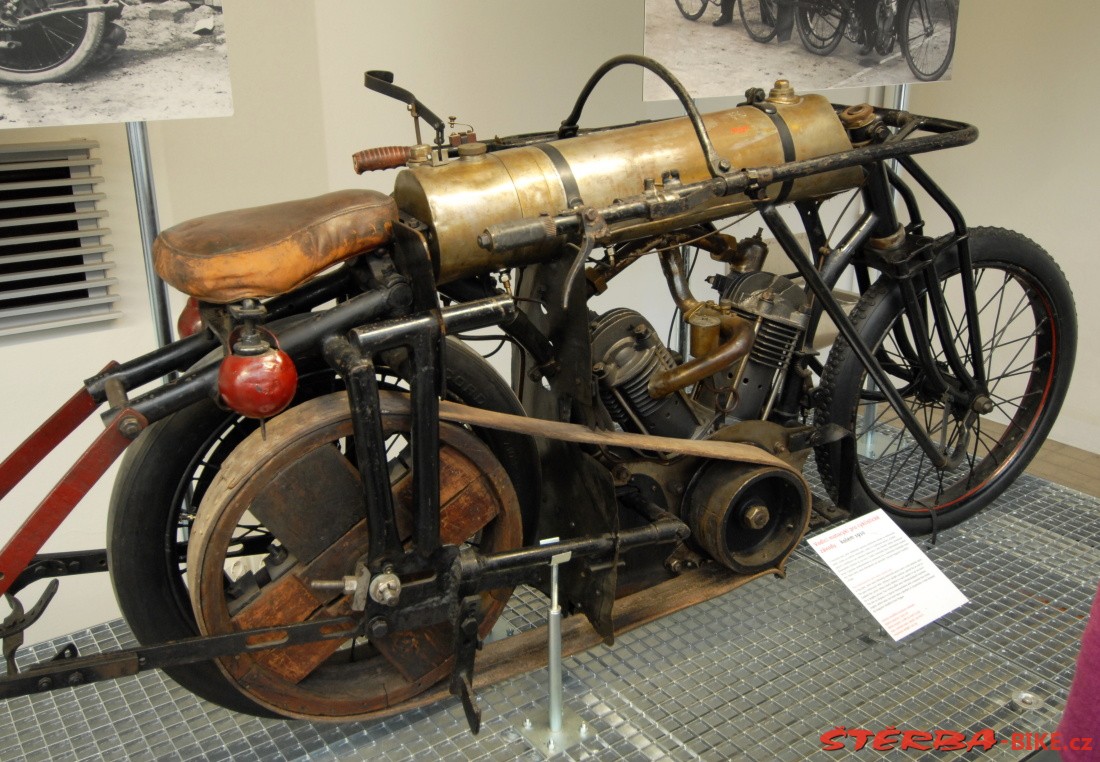

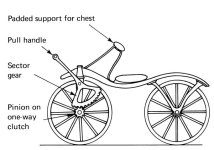

The earliest precursor to both scooters and motorcycles was the 1894 Hildebrand and Wolfmuller, the first motorized two-wheel vehicle sold commercially. Yet while the primitive vehicle used a scooter-style step-through frame design, it did not directly influence the evolution of most two-wheeled vehicles other than to demonstrate that a two-wheel layout was viable and that there was a potential market for vehicles configured as such. Instead, motorcycles evolved directly from bicycles and shared their large wheels, vertical frames, and saddle-like seats. In contrast, scooters evolved from the kick-push children’s toys with which they shared their name. These vehicles had a single small diameter wheel at each end of a platform about the size of a large skateboard upon which the rider stood. A pole extended upward from the front wheel to the handlebars for directional control. Ultimately, the word “motor” was added ahead of the word “scooter” to distinguish them from their unpowered counterparts. Today a motor scooter is normally defined as a small two-wheeled vehicle with small wheels, a small engine, a step-through frame, and a platform upon which a rider can rest his or her feet.

From the beginning, no vehicle has been simpler to operate or easier to get onto than a scooter and they did not require a great deal of gear and specialized apparel to wear while operating. Motor scooters could be driven in places too small for even motorcycles and were much cheaper to buy and operate than automobiles. The step-through frame and foot platform meant that all a rider had to do to mount a scooter was take one small step up, turn to face forward, and sit down. It was not necessary to throw one’s leg over a high mounted frame member or gas tank, a maneuver that women during the early years of powered transportation would have found impossible to execute because of their long dresses and untold layers of bulky undergarments. Like most consumer goods that embodied newly introduced technologies, scooters were purchased primarily by wealthy motorists to use as local runabouts when they were first marketed during the 1910s.

The American 1915 Autoped is regarded by most historians as the first true scooter. Looking little different than the child’s toy to which it was so closely related, the New York-built Autoped was powered by a tiny 1.5-horspower, one-cylinder motor attached to the left side of the front wheel. To accelerate, one simply had to push the handlebar stalk forward while pulling it back slowed the engine and engaged the brake. The fact that a brake was fitted to the front wheel only was a minor concern because of their severely limited performance; top speed on level ground was just 18 miles per hour. Autopeds appealed to early buyers because they were nimble, easy to maneuver, and easy to mount. They were also easy to store and, because the handlebars could be folded down, it was theoretically possible to carry the device with one hand like a suitcase. Though primitive compared to later scooters, the Autoped was as cutting edge during the 1910s as the Segue is today. It would have been difficult for observers not to be amazed as the new conveyance buzzed past them and down the road, usually with a smug, well-dressed rider aboard. They were greatly admired abroad and Krupp made them under license in Germany from 1919 to 1922. Like electric cars, Autopeds were heavily promoted to women because they could ride them while wearing regular street clothes, including large hats and the long dresses that were then in fashion, and their limited range and poor performance was not an issue.

The large majority of early motor scooter buyers lived in cities with smooth paved streets that did not have the bumps or deep ruts in which very small wheels could get caught and possibly cause injury to the rider or damage to the machinery. That scooters were significantly less powerful, far slower, and more delicate than the average full-size car or motorcycle was actually appealing to women of the day, most of who would have found themselves intimidated by anything larger or more massive and unwieldy. Eventually the tiny platforms sprouted seats for greater comfort (and marketability) and horns and lights for safety in traffic and night riding. Despite the obvious advantages, scooters did not become popular during the 1920s in part because most people lived in neighborhoods where they had easy access to employment, shopping, and businesses, and an integrated public transportation systems to take them where they needed to go. For the vast majority of the population, a scooter—or any other means of personal transportation—would have been superfluous.

English entrepreneurs spearheaded a resurgence in scooter manufacturing for a brief period after World War I as a large number of thrm entered the scooter building business in an effort to utilize some of the excess production capacity that had been created for the construction of weapons of war. Electric lighting, new suspension systems, and multiple speed gear boxes were soon incorporated into scooter designs. Yet while the little vehicles evolved rapidly, the placement of their engines would not be standardized for several years. While early scooters like the Autoped had engines that attached directly to the front wheel, later models from other manufacturers (like the 1917 Kenilworth) had engines mounted low and ahead of the rider’s feet and others (such as the 1919 ABC Scootamota) were designed with their tiny engines immediately above the rear wheel. One American manufacturer, Briggs & Stratton, built theirs with the single-cylinder engine attached directly to the side of the rear wheel, a placement that simplified the drive system although it added significantly to unsprung weight and affected stability and ride quality.

By the early 1920s, virtually all scooters were equipped with seats and an ever increasing number were designed with engines located under the rider, an area that would otherwise have gone unused. Such an engine placement allowed for a low center of gravity and permitted stylists to create attractive metal bodywork that served as both a covering for the engine and a support for the seat. Some progressive designers eventually extended this sheet metal shroud forward at the bottom to form the foot platform and splash guard. A few manufacturers took styling more seriously than others and one unusually advanced design, the British 1920 Unibus, was so well integrated that it could easily be mistaken for a 1950s German model. As it did with automobiles, the overall appearance of scooters slowly progressed from a collection of disparate, unattractive parts to a unified, neatly packaged whole. Unfortunately, the reputation of most early scooters was damaged by an overabundance of bad handling, poorly designed, and weakly constructed examples that had been rushed to market to take advantage of the then current fad. And while a small number of quality manufacturers continued their pioneering efforts, their models were too expensive to compete and during the mid-1920s scooters all but disappeared from the market for the second time.

The world wide lull in scooter production continued until almost the end of the Great Depression, when a newly emerging class of American motorists created a fresh demand for the blend of distinction, utility, and enjoyment that scooters offered. During this period, domestic manufacturers rose to the forefront of motor scooter design and innovation, and a large number of scooter builders were established in the Midwest and California. One of the first scooters to rise to national prominence was the Salsbury, brainchild of minimalist transport pioneer E. Foster Salsbury. Working first in the back room of his brother’s heating and plumbing shop in Oakland, California before relocating to Los Angeles, Salsbury was reportedly inspired to create his first scooter when he noticed famed aviatrix Amelia Earhart riding one of the few remaining operational Autopeds around the Lockheed Airport in Burbank. But whereas the Autoped of the mid-1910s was intended as a plaything for the affluent, Salsbury scooters of the mid-1930s were intended to mobilize the masses by offering inexpensive, reliable transportation for average people to take to the increasing number of places that were too far to walk, but too close to drive.

Breaking with American scooter tradition, Salsbury equipped their first scooter, the 1935 Motor Glide, with a seat for the rider. It also had an exposed engine with a primitive roller drive system that easily lost grip on wet surfaces. Predictably, very few were manufactured before it was replaced with a model having direct drive and a seat mounted on an attractively designed metal shroud that surrounded the engine. By 1937 Salsbury was building what looked like a bar stool on wheels equipped with a continuously variable transmission, the first ever on a scooter. Foster Salsbury’s early success inspired other manufacturers to join the fray and the Salsbury Motor Glide was soon sharing the market with scooters manufactured by Powell (Pomona, California), Moto-Scoot (Chicago, Illinois), Cushman (Lincoln, Nebraska), and dozens of others. Included among these manufacturers, though often absent from formal listings, were those that offered assemble-it-yourself models like the Renmor Constructa-Scoot, which could be purchased with or without an engine. Catering to the lowest end of the market, some scooter designers offered only plans for sale to those who were (or thought they were) handy enough to build a scooter from scratch using their own parts, although it is extremely unlikely that many did despite their good intentions. By the late 1930s, aficionados came to consider scooters as important as clothes and jewelry in proclaiming their status and very few wanted to be seen riding on anything that looked rickety or homemade.

Advertisements and articles in magazines such as Popular Mechanics helped to propagate the excitement surrounding scooters among adults even as they whetted the appetites of early adolescents anxious to experience the thrill of operating a motorized vehicle that seemed to be sized just for them. Many photographs showed attractive women riding scooters (often Salsburys) in the California sunshine or employing them as mechanical ponies for games of parking lot polo. Hollywood actors and actresses contributed to scooter popularity—and glamour—by being photographed on them as they clowned for the camera or by using them to traverse expansive movie studio lots. And like Amelia Earhart did with her Autoped, airplane pilots and airport workers across the United States began to use scooters to cover large stretches of tarmac, which they were often obliged to do. This utility was later appreciated by World War II pilots, ground crews, and messengers, most of who were spared having to walk the long, tiring distances to, from, and between airplane hangars, offices, mess halls, barracks, and the aircraft.

During World War II, some specially designed motor scooters took flight so that they could be airlifted behind enemy lines and dropped by parachute with Army Airborne troops who then used them for basic ground transportation when they landed. Sometimes called parascooters, they were built by companies such as Cushman in America, Welbike in Great Britain, and Volugrafo in Italy. Other scooters were deployed on the ground, serving as tiny troop movers, supply vehicles, and weapons carriers. But whatever the use, they were usually stripped of all comfort and convenience amenities, equipped with heavy duty tires and other components, and painted the preferred color of their country’s military. Having developed a basic kind of automatic transmission of its own, Cushman eventually replaced Salsbury as the dominant American scooter manufacturer, building as many as 300 units per day for use by both military personnel and civilians who found it virtually impossible to get around any other way during the days of gas rationing, tire shortages, and other limitations related to private transportation.

Motor scooter sales boomed after World War II and large numbers were built all over the world, though the reasons for their popularity varied from country to country and region to region. In America, the pent up demand for anything motorized created a sellers’ market for all forms of personal transportation and after the armistice a considerable number of newly established manufacturers invested the money they earned during the conflict into the business of building vehicles of all kinds. Like their counterparts in the automobile industry, these new scooter manufacturers seized what they believed was the ideal opportunity to launch a new high-demand consumer product. Anticipating a brisk market, some companies, including jukebox manufacturer Rock-Ola, diversified into scooter building. Regrettably, most new motor scooter manufacturers misread the market and the transportation revolution they were planning for did not materialize. As the American economy grew beyond all expectations, the very large majority of domestic motorists developed a taste for ever more advanced styling and engineering along with a desire to display their increasing affluence. For them, scooter ownership was not compatible with these new priorities and demand plummeted. Even the space age look of the swoopy Salsbury Model 85 could not save it and by 1948 the firm that had pioneered scooter design and manufacturing was unceremoniously forced out of business.

Overseas, the economy of most countries after the war was shattered and the mood was somber. Whether Allied or Axis, the warring nations had to deal with a decimated manufacturing infrastructure, a scarcity of raw materials, and, for some, new rules about what they could and could not produce. In Germany, Italy, and Japan, military aircraft manufacturers like Heinkel, Piaggio, and Mitsubishi were prohibited from building aircraft or anything else with the potential to be used as a weapon of war. Desperate to remain in the manufacturing business, a number of these firms turned to building motor scooters, unwittingly creating some of the most iconic vehicles of all time. The designers derived their inspiration from a variety of sources and embodied in their products the kind of progressive, yet rational styling that American scooters had always lacked. Foremost among them, the Italian Vespa was introduced in 1946 by Piaggio, a firm that built airplane engines during the war, but needed a low cost product with mass appeal to remain viable in the postwar environment. Their now legendary motor scooters helped put Italy back on wheels and by 1949 Italian roads were buzzing with an estimated 110,000 of the tiny vehicles, a large proportion of them Vespas. Thanks in part to the Italian government aid also enjoyed by Vespa, Ferdinando Innocenti was able to introduce his Lambretta in 1947, setting the stage for their now famous rivalry with Vespa.

American investment aided in the rebuilding of the German manufacturing industry and motor scooters were an important contributor to the reindustrialization of the nation. A number of scooter manufacturing operations were established by firms that were not allowed to return to building war materiel such as Heinkel (a former aircraft manufacturer) and Simson (a former firearms manufacturer). Their products, like those of most other German scooter manufacturers, were large, heavy, and fast. And while such qualities made them ideal for travelling long distances on long, straight autobahns, they were incompatible with the needs of motorists from other European nations forced to contend with cobblestone city streets and twisty country lanes. A relatively small number were sold outside of Germany as a result. French companies also produced scooters that were little known outside their native land as did British scooter manufacturers, who tailored their products too specifically for the conservative home market to be appealing to international buyers. Operating in near isolation, Eastern European motor scooter manufacturers found themselves building the only type of vehicles that the majority of citizens in their home markets could afford, many of which came to embody the Western design excesses they supposedly disapproved of.

As in Germany and Italy, Japanese industry was not permitted by the occupying forces to manufacture any product that could potentially be used as a weapon of war and many former airplane and armament manufacturers turned to building scooters. Fuji Sangyo, an offshoot of the defunct Nakajima Aircraft Company (builders of bombers, fighters, and interceptors during the war), was reborn as Fuji Heavy Industries and began building Fuji Rabbit scooters in 1946. These scooters used a number of surplus aircraft parts, including the tail wheel of a bomber that had been re-purposed as the front wheel of the scooter. Mitsubishi (manufacturers of the legendary Zero fighter plane) introduced their first scooter, the Silver Pigeon, also in 1946. Both firms’ designs borrowed heavily from those of the Powell and Salsbury scooters that had been brought to Japan by United States military personnel, giving them an unexpected, but strong California connection. Fuji and Mitsubishi scooter production continued into the 1960s with a large proportion of their early production going to their insatiable home market, a situation that temporarily allowed European and American manufacturers the chance to operate without significant competition from the East.

When their home market became saturated, Japanese manufacturers expanded their reach to include North America, with disastrous consequences to the few remaining domestic scooter manufacturers. Period advertisements accurately portrayed Japanese scooters as the fun, friendly and reliable vehicles that they were and attracted the attention of a market segment not normally associated with scooter ownership. Even Vespa could not compete against the low cost, high quality products from Honda, Yamaha, and Suzuki, and withdrew from the American market in 1979. Having added mini bikes and mopeds to their product mixes over time, manufacturers from Japan enjoyed great success in the United States, but could not possibly have predicted the wave of nostalgia that would sweep North America during the last decade of the twentieth century. Just as cars of the 1950s and 1960s have recaptured the imaginations of American motorists of all ages, so have scooters. Fond desires for the trappings of a bygone era coupled with unpredictable fuel prices, concerns for the environment, and an enduring desire to look as stylish as possible regardless of prevailing circumstances, have created a brisk demand for the kind of economy, social responsibility, and chic that motor scooters now represent. Models with paired front and rear wheels for stability, permanent canopies for weather protection, and battery electric power for economy have become commonplace and manufacturers from China, India and Korea now vie for shares of the lucrative American market. Vespa has even returned to the United States, remaining strong despite the flood of cheaper, look-alike retro models.

California remains one of the top scooter markets in the United States and a large number of brands eagerly battle for market share in the Southland despite rigorous statewide emissions standards that have driven up the cost of manufacturing. Scooters have become a realistic alternative to automobiles for many motorists who have grown weary of traffic snarls, high gas prices, and difficult parking. Riding a scooter can also be a source of fun and is entertaining in ways that even the most expensive cars cannot be. Like the Autopeds of almost a century ago, modern motor scooters offer a sense of freedom and independence and buzzing around on one tends to confer on the rider a kind of youthful sophistication not associated with any other type of two wheel vehicle. Scooters seem to have become the mechanical equivalent of the bow tie; they are not right for everybody, but those who dare to embrace them will earn a measure of respect, distinction, and personal satisfaction known to few others.